Hundreds of thousands of Americans suffer back pain related to vertebral compression fractures (VCF) every year, in many cases related to osteoporosis, but the spine specialist community at large has not agreed upon the most effective clinical care pathway.1 Vertebral augmentation procedures — vertebroplasty (VP) and balloon kyphoplasty (BKP) — were developed to treat VCFs due to osteoporosis, cancer or, at times benign lesions of bone. However two 2009 studies cast vertebroplasty in a negative light, and procedural volumes dropped nationwide.

Joshua Hirsch, MD, vice chair of procedural services as well as chief of the neurointerventional spine service at Boston-based Massachusetts General Hospital, led multiple studies investigating vertebral augmentation and is committed to expanding access to care for properly selected VCF patients. He co-authored an article published last year in The Spine Journal titled “Management of vertebral fragility fractures: a clinical care pathway developed by a multispecialty panel using the RAND™/UCLA Appropriateness Method,” which brought together multidisciplinary specialists to develop the foundation for a VCF clinical care pathway.2

Joshua Hirsch, MD, vice chair of procedural services as well as chief of the neurointerventional spine service at Boston-based Massachusetts General Hospital, led multiple studies investigating vertebral augmentation and is committed to expanding access to care for properly selected VCF patients. He co-authored an article published last year in The Spine Journal titled “Management of vertebral fragility fractures: a clinical care pathway developed by a multispecialty panel using the RAND™/UCLA Appropriateness Method,” which brought together multidisciplinary specialists to develop the foundation for a VCF clinical care pathway.2

“The purpose of this exercise was to look at a variety of scenarios and design a system where [healthcare providers] could see a patient and recommend the appropriate next steps, whether that’s conservative therapy, imaging or vertebral augmentation,” said Dr. Hirsch.

This article briefly outlines influential studies on vertebral augmentation and offers discussion on a clinical care pathway for VCF patients.

History

In 2009, two studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine compared vertebral augmentation to an active sham control.3 In the smaller of the two trials from Australia, the authors outlined findings from a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, active sham-controlled trial comparing vertebroplasty to a sham procedure in 71 patients. Study authors reported results were similar between both groups.4

The second study, the INVEST trial, included 131 patients with painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. The patients were randomized into groups that underwent vertebroplasty or a simulated procedure without cement, and patients could cross over between study groups one month after beginning treatment. In this study, authors concluded both groups had similar improvement.5

As mentioned above, Dr. Hirsch and collaborators including Kevin Ong, PhD, a principal engineer with Exponent, examined the steep reduction in vertebral augmentation volume over the five years after the articles were published.6 Based on Medicare data gathered from 2005 to 2014, in the five years prior to publication of the NEJM studies, 24 percent of VCF patients underwent balloon kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty. This dropped to 14 percent in the five years after the studies were published. Additionally, Dr. Hirsch pointed out, “The 10-year risk of mortality for patients with VCF was 85.1 percent, which is quite high.”

Several recent, large clinical studies followed for at least 12 months after VCF have concluded that mortality rates following VCFs are significantly higher for patients treated conservatively versus VP or BKP, while other studies have concluded no difference. Five studies concluded that patients treated with vertebral augmentation experienced lower mortality risk than patients treated with non-surgical management.7, a, b, c, d, e, f

For more information on VCF mortality risk, visit medtronic.com/bkpmortality

Developing a clinical care pathway

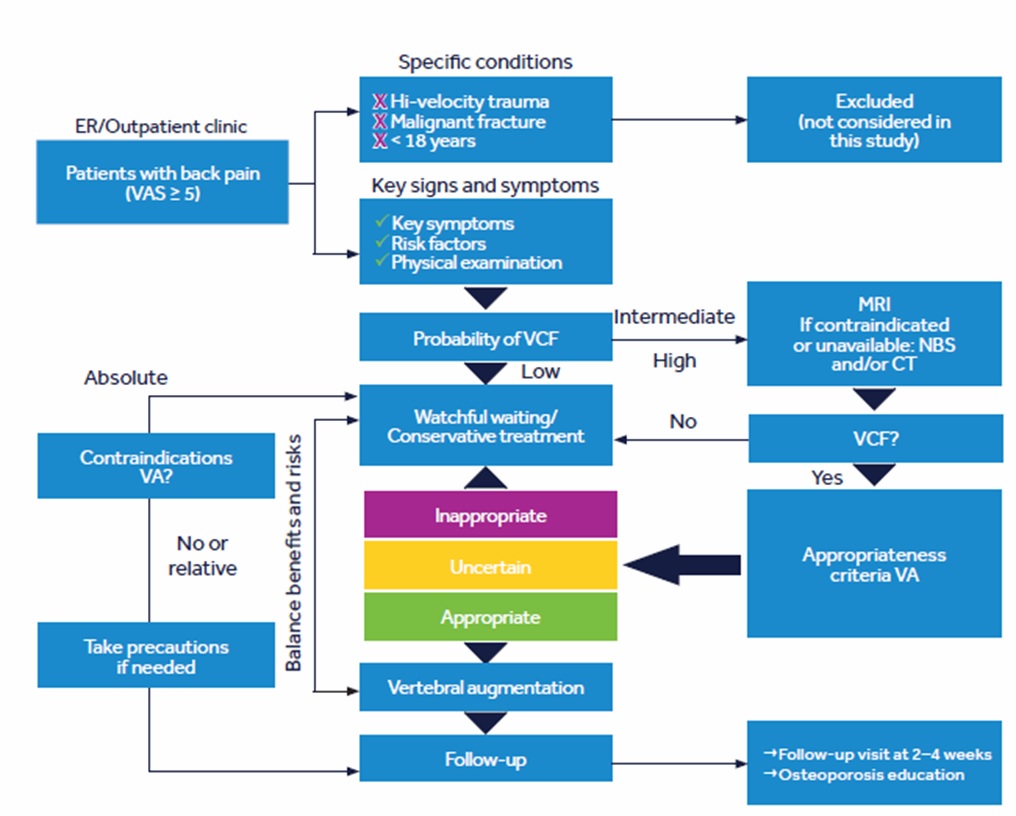

Patients with VCF see a wide variety of practitioners with varying levels of experience regarding the full range of treatment options available. Dr. Hirsch and colleagues — including orthopedic and neurosurgeons, interventional radiologists and pain specialists — wished to develop a clinical care pathway that would be helpful to a broad range of practitioners across that care continuum. This multispecialty group used the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method to develop patient-specific recommendations for VCF clinical care pathway. The clinicians reviewed 20 signs and symptoms for VCF and considered relevance of five diagnostic procedures for 576 clinical scenarios; they also considered six aspects of follow-up care. After two rounds of individual ratings and two plenary discussion sessions, the panel developed a recommended clinical care pathway for VCF patients.8

One challenge the panel specifically wished to address was the number of entry points VCF patients have into the healthcare system. Back pain patients who seek a referral from a primary care provider may be directed to non-surgical treatment options (e.g. physical therapist, an occupational therapist or given an opioid prescription). The provider these patients are seeing may not be familiar with vertebral augmentation or understand treatment options when conservative therapy fails. Other patients who arrive at the emergency room in pain may undergo radiology tests or treatment from non-spine specialists who do not properly identify or diagnose VCFs.

One challenge the panel specifically wished to address was the number of entry points VCF patients have into the healthcare system. Back pain patients who seek a referral from a primary care provider may be directed to non-surgical treatment options (e.g. physical therapist, an occupational therapist or given an opioid prescription). The provider these patients are seeing may not be familiar with vertebral augmentation or understand treatment options when conservative therapy fails. Other patients who arrive at the emergency room in pain may undergo radiology tests or treatment from non-spine specialists who do not properly identify or diagnose VCFs.

“There are so many points where vertebral compression fracture patients intersect with the healthcare system that it’s difficult for everyone to know what the optimized care plan might be,” Dr. Hirsch said. “There are a great many patients with these fractures that aren’t referred to interventional specialists who would benefit from vertebral augmentation. The purpose of our panel was to look at a variety of scenarios and design a system where clinicians that see the patient initially can make an informed decision about the appropriate next steps.”

Throughout the rating process and discussions, the multidisciplinary panel found areas where there was acceptance and discordance, as well as gray areas where not everyone agreed. In the final article, the panel recommended VCF patients:

- Receive a referral to bone density and osteoporosis education.

- Participate in a program focused on osteoporosis treatment and prevention.

- If symptoms persist at the follow-up visit, undergo additional imaging.

The panel also created clinical care pathways based on advanced imaging results and symptom improvement or decline. In addition to recommending patients with severe pain and probability of VCF undergo advanced imaging with MRI, CT scan or bone scan, the panel came to consensus about appropriate treatment and follow-up protocol. The panel suggested a shorter wait time between diagnosis and pursuing interventional treatment.9

“Historically, clinicians waited for weeks to see whether physical and/or other elements of conservative therapy would fail before moving on to more aggressive treatment,” Dr. Hirsch said. “However, in this study the experts believed by and large that waiting an artificial length of time while patients’ health declined wasn’t a good thing. It was interesting to see expert consensus solidify as an idea that hasn’t been previously articulated.”

The RAND/UCLA paper provides clinicians with an evidence-based clinical care pathway to identify symptomatic patients and direct them to the most appropriate care. The fact that the report was double-blinded doesn’t mitigate that the panel process has subjective input. However, it can be noted that strict adherence by the multidisciplinary experts to adopt the RAND™ methodology process based on published clinical evidence and expertise was observed.

VCF Clinical Care Pathway project was supported by a grant from Medtronic. However, Medtronic was not involved in the design or execution of the project, nor the preparation and review of this manuscript. Names of panel members were not disclosed to the sponsor, and panel members were not informed about the identity of the sponsor before submission of the manuscript.

Clinical patient results

A strong body of literature supports vertebral augmentation for VCF patients, and clinicians across the treatment spectrum agree early intervention is appropriate in selected patients. As more clinicians and non-spine specialists are educated about diagnosing and treating VCF, patients will have increased access to interventional treatment options.

“Patients tend to be extremely strong advocates of the procedure,” Dr. Hirsch said. “It’s also gratifying for the physician due to the patient outcomes; it’s a very rewarding procedure, professionally.”

Hospitals and health systems across the country are at various stages of integrated care for back and neck pain. Whereas the infrastructure already exists at larger, multidisciplinary organizations to implement a clinical care pathway, smaller organizations can influence referral patterns and outcomes by implementing a similar structure.

“Institutions can develop their own clinical care pathways and successfully gain consensus at an organizational level. There is also a societal opportunity where big organizations that represent multiple specialists can bring together disparate experts to develop care pathways,” Dr. Hirsch said. “Our recommendations provide a substrate for big and small institutions, providers and networks to standardize referral patterns and care pathways for vulnerable patients. If we can optimize their care pathway on the macroscopic level, it will have an affect at the patient care level.”

About Balloon Kyphoplasty (BKP)

BKP is a minimally invasive procedure for the treatment of pathological fractures of the vertebral body due to osteoporosis, cancer, or benign lesion. The complication rate with BKP has been demonstrated to be low. There are risks associated with the procedure (e.g., cement extravasation), including serious complications, and though rare, some of which may be fatal. Risks of acrylic bone cements include cement leakage, which may cause tissue damage, nerve or circulatory problems, and other serious adverse events, such as: cardiac arrest, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, or cardiac embolism.

For complete information regarding indications for use, contraindications, warnings, precautions, adverse events, and methods of use, please reference the devices’ Instructions for Use included with the product.

For more information on VCF Carepathway visit: medtronic.com/vcfcarepathway

For more information on VC Mortality Risk visit: medtronic.com/bkpmortality

References

1 Hirsch JA, Beall DP, Chambers MR, et al. Management of vertebral fragility fractures: a clinical care pathway developed by a multispecialty panel using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Spine J. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.07.025.

2 Hirsch JA, et. al.

3 Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P. Wriedt C, et al. A Randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J med 2009;361: 557-68. ; Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, Turner JA, Wilson DJ, Diamond TH, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med 2009;361: 569-79.

4 Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P. Wriedt C, et al. A Randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J med 2009;361: 557-68.

5 Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, Turner JA, Wilson DJ, Diamond TH, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med 2009;361: 569-79.

6 Ong KL, Beall DP, Frohbergh M, Lau E, Hirsch JA. Were VCF patients at higher risk of mortality following the 2009 publication of vertebroplasty ‘sham’ trials? Osteoporos Int 2018;29:375-83.

7 (a) Ong KL, Beall DP, Frohbergh M et al. Were VCF patients at higher risk of mortality following the 2009 publication of the vertebroplasty “sham” trials. Osteoporos Int. 2017 Oct 24. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4281-z. (b) Edidin AA, Ong KL, Lau E, Kurtz SM. Mortality risk for operated and nonoperated vertebral fracture patients in the Medicare population. J Bone Miner Res. 2011 Jul;26(7):1617-1626. doi: 10.1002/JBMR.353. PubMed PMID: 21308780. (c) Chen AT, Cohen DB, Skolasky RL. Impact of nonoperative treatment, vertebroplasty, and kyphoplasty on survival and morbidity after vertebral compression fracture in the Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Oct 2;95(19):1729-1736. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01649. PubMed PMID: 24088964. (d) Lange A, Kasperk C, Alvares L, Sauermann S, Braun S. Survival and cost comparison of kyphoplasty and percutaneous vertebroplasty using German claims data. Spine. 2014 Feb 15;39(4): 318-326. doi: 10.1097/BRS.00135. PubMed PMID: 24299715.(e) Edidin AA, Ong KL, Lau E, Kurtz SM. Morbidity and mortality after vertebral fractures: comparison of vertebral augmentation and non-operative management in the Medicare population. Spine. 2015 Aug 1;40(15):1228-1241. doi: 10.1097. PubMed PMID: 26020845. (f) McCullough BJ, Comstock BA, Deyo RA, Kreuter W, Jarvik JG. Major medical outcomes with spinal augmentation vs. conservative therapy. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Sep 9;173(16):1514-1521. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8725. PubMed PMID: 23836009; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4023124.

8 Hirsch JA, et al.

9 Hirsch JA, et al.

.jpg) PMD022530-1.0 / UC201912667 EN

PMD022530-1.0 / UC201912667 EN